EXTREME HEAT HAS UNEQUAL IMPACTS ON DIFFERENT NEIGHBORHOODS

Most of us know which parts of the city are hotter... so what? As our interactive maps show, what matters is that the hotter areas also tend to be low-income neighborhoods with more people of color. Research shows that this overlap is not a coincidence. Factors like race, income level, housing, neighborhood status (including its history) all matter in making one more susceptible to extreme heat-related risks.

We've picked three examples - redlining, health disparities, and greenspace access - to show the intersecting and compounding factors that both contribute to, and exacerbate, the disproportionate heat-related health impacts on people already marginalized.

Research suggests that the historic, racist patterns of institutionalized discrimination and disinvestment - such as redlining - still manifest in the current landscape of vulnerability to heat across cities in the US.

Redlining refers to the federal government-led process in the 1930s by which Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) created 'residential security maps' delineating neighborhoods into different categories to indicate risk levels for giving out loans:

- most desirable (lighter red);

- slightly less desirable;

- declining neighborhoods;

- undesirable (darker red).

The categories were assigned primarily based on the neighborhood's socio-demographic composition, and areas with high percentages of low-income immigrant or Black residents were marked as 'D' - 'undesirable', colored in dark red.

Redlining is associated with a wide range of present-day adverse outcomes, including disproportionate vulnerability to heat, adverse health outcomes, higher asthma rates, birth outcomes, and cancer diagnoses, among others.

For information specific to NYC, see Gaffud, 20211

For examples of other cities, see Schinasi et al., 20222; Wilson, 20203.

In areas already marginalized along race and class lines, heat-related impacts are not only about temperature and humidity. Those with pre-existing conditions are more susceptible to heat-related illness and death, as high heat can contribute to deaths from heart attacks, strokes, and other forms of cardiovascular disease. High heat combined with air pollution can also be deadly, particularly for those with respiratory problems.

Neighborhoods that are hotter also tend to have higher rates of pre-existing health conditions, leaving residents all the more susceptible to heat-related illness and death.

These stark health disparities are not coincidental. These areas are more likely to have higher rates of pollution due to a concentration of less-desirable infrastructure, such as industry, highways, and waste transfer facilities. A lower average income also means residents do not have access to good quality, consistent health care.

The Mott Haven-Port Morris area of the South Bronx is one of these areas. Known as 'Asthma Alley'4, it experiences some of the worst congestion in the US. This means that residents are more likely to have existing health conditions such as asthma, which is made worse by extreme heat. Extreme temperature can cause air to become stagnant, trapping pollutants in the air, which can cause an asthma flare-up, which causes your airways to swell, making it hard to breathe.

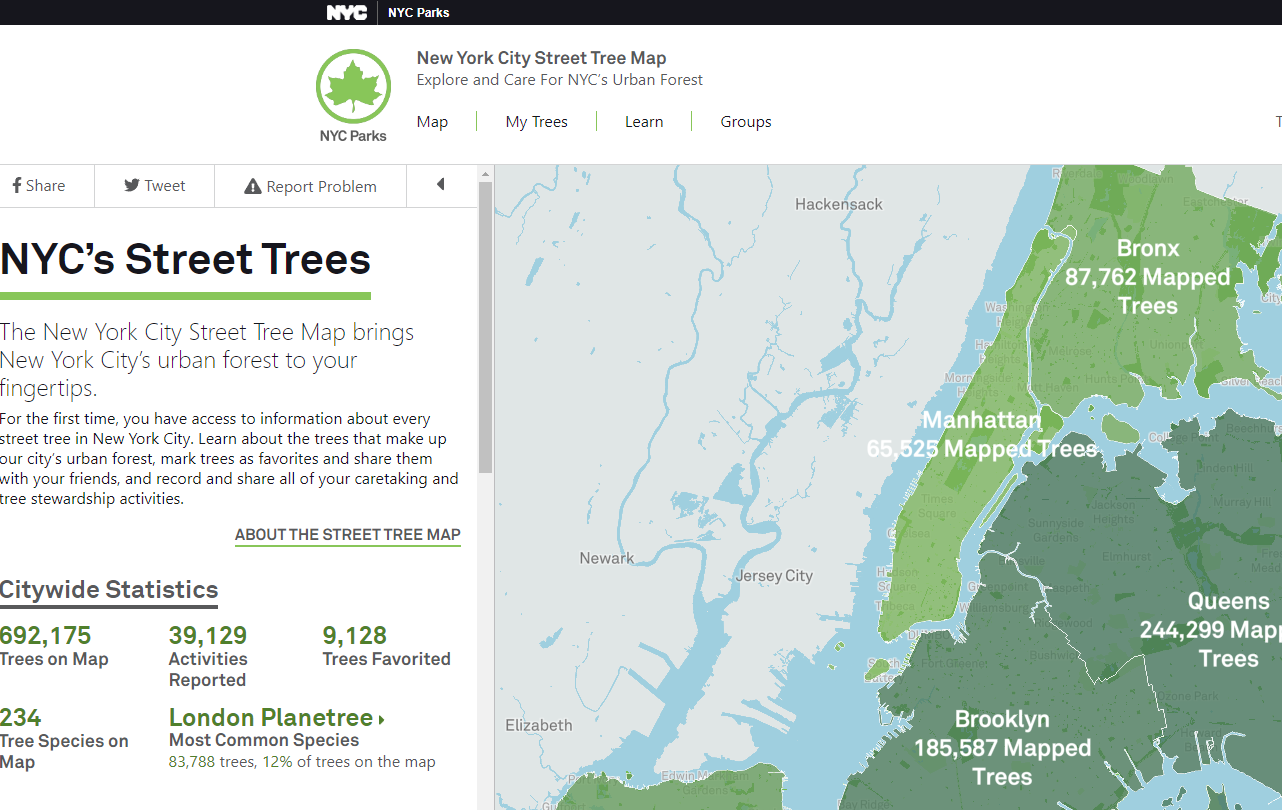

Having access to greenspace (tree canopy, parks) makes a significant difference in buffering again extreme heat. Trees and vegatation are effective in reducing the urban heat island effect by lowering surface and air temperatures by 20-45°F5. However, neighborhoods of low-income and people of color have less greenspace on average compared to the white, more affluent areas. This means yet another buffer against extreme heat that marginalized populations do not have access to. For information specific to NYC, see Urofsky & Parks, 20206

- 1 Gaffud J (2021) New York City's Redlining History Today. Available here.

- 2 Schinasi LH, Kanungo C, Christman Z et al. (2022) Associations Between Historical Redlining and Present-Day Heat Vulnerability Housing and Land Cover Characteristics in Philadelphia, PA. J Urban Health 99, 134-145 DOI: 10.1007/s11524-021-00602-6.

- 3 Wilson B (2020) Urban heat management and the legacy of redlining. Journal of the American Planning Association 86(4) DOI: 10.1080/01944363.2020.1759127.

- 4 Kilani H (2019 April 4) 'Asthma alley': Why minorities bear burden of pollution inequity caused by white people. The Guardian. Available here.

- 5 Akbari H, Kurn DM, Bretz SE & Hanford JW (1997) Peak power and cooling energy savings of shade trees. Energy and Buildings 25(2): 139-148.

- 6 Urofsky E & Parks RM (2020) Public green spaces: Racism, heat, and barriers to access. WEACT for Environmental Justice. Available here.

- 7 Gordon A (2020 April 22) The fight for green neighborhoods is a matter of life or death. VICE. Available here.